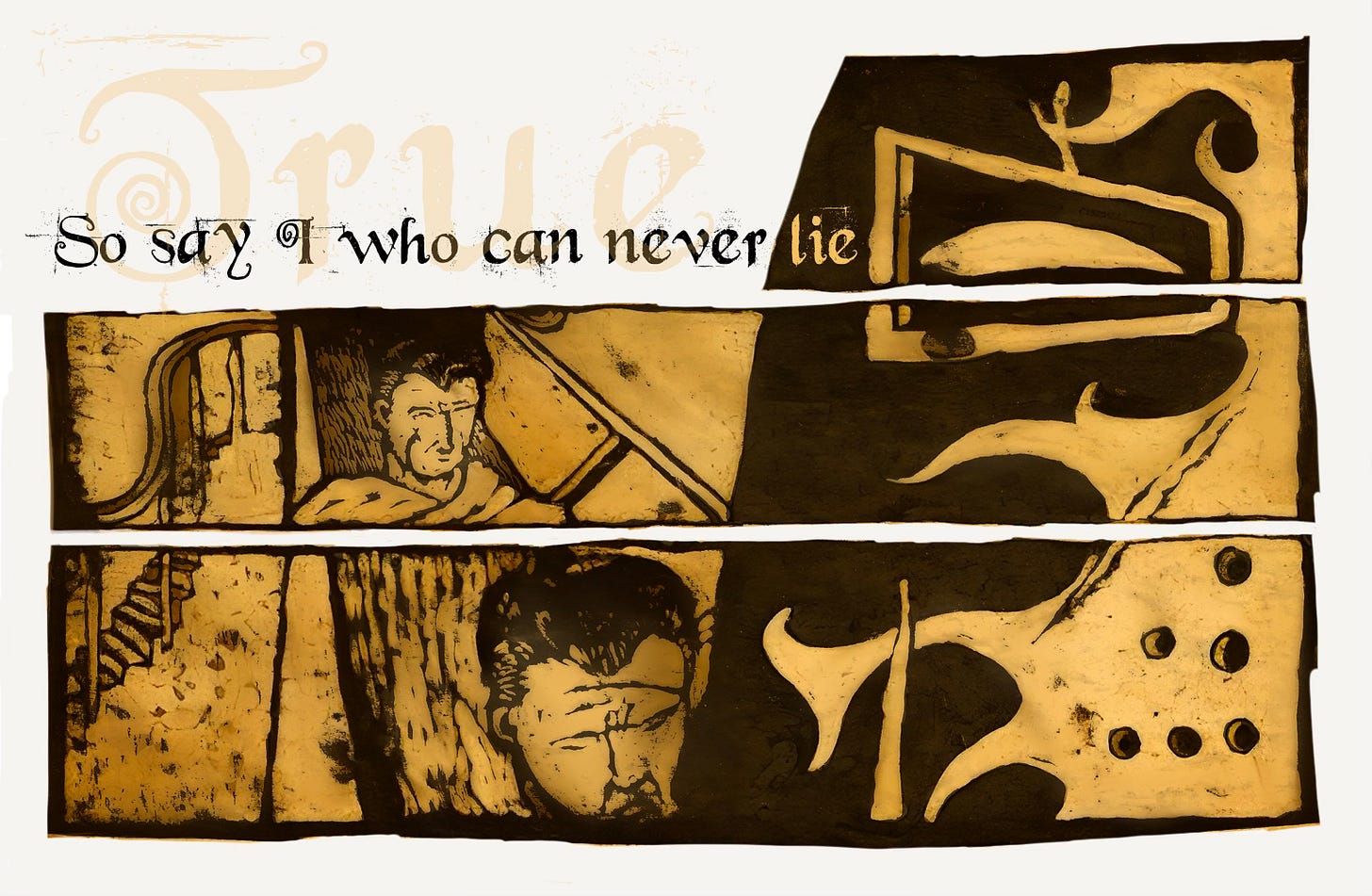

“Tho Thomas the lyar thou callest me

A sooth tale I shall tell thee!”

I must number amongst those who are still fascinated by Thomas the Rhymer. Despite having died several hundred years ago, I find myself beguiled by his story. He is a figure shrouded in mystery: a prophet and a bard, whose name crops up in several locations across Scotland. Through the centuries his character has been woven into the fabric of Scottish folklore.

Thome Rymour de Ercildune was born and raised near the town of Earlston, not far from Melrose, in the Scottish Borders. The hamlet was once known as Ercildune and was once pressed between the old kingdom of Strathclyde and that of Bernicia. Rhymer’s family home was a substantial stone tower-house, near east bank of the River Leader. Like many mythic characters he has a number of appellations, Laird Learmount and True Thomas among them. The Gaelic speaking Highlanders knew him as, mac na mna mairbh or ‘son of a dead woman’. The legend has it that his mother died during the labours of childbirth, and the babe was cut from her womb. Some say that it was only after his mother was interred, that an infant’s cry came from her coffin. When it was opened the child was within. Although there are no records of his birth or death, it’s reckoned that he lived between 1220 and 1298 AD – a time when Scotland balanced upon a knife’s edge between the power of England and the constant threat of Norse attack.

The lands around Thomas’ home are rich in ancient lore. There is Elwand Glen (now known as Ellwyn Glen), the Fairy Dean that Walter Scott called a refuge of the elfin race, which lies where the river Allan meets the Tweed. The area abounds with fairy paths, fairy stones and, drawing the eye of any traveller to the region, the Eildon Hills. The Romans named this hill of three peaks, Trimontium. Likewise, this feature doubtlessly secured it as a sacred place for the Celts – in whose stories and art triples abound! There’s evidence that the hills were a site of interest back in the Bronze Age too. No wonder then that it was said to be hollow: that Eildon was a síd, Shÿen or faerie hill was a popular belief around the locale.

One fable relates how a trader from Canonbie, called Dick, was approached by a mysterious stranger, who offered to buy his horses. The merchant, hungry for a deal, was led to a small knoll on the heights of Eildon, known as the Lucken Hare. This was a place where witches were said to hold their midnight meetings. But on this occasion an open door was set in the mound, into which the stranger disappeared. Canonbie Dick followed, imagining the feel of the gold in his purse. They travelled deep into the earth, beneath the hills, until they came across a huge cavern, beset with wooden stalls. In each was a black warhorse, and beside each destrier a knight lay asleep – none other than King Arthur and his knights! Upon an ancient table a great sword lay in its sheath. Above it, a horn was suspended. Suddenly the stranger’s voice boomed out, echoing through the chamber, “He that blows the horn and draws the sword will, if his heart be true, be king of Britain – so speaks the one who cannot lie. All depends on your courage and which you pick first”. Dick, realising his guide is none other than Thomas Rhymer, was overcome with fear. Should he pick the horn or the sword first? An image of the sword flashed in his mind’s eye, but he hesitated… what if drawing it from its scabbard incurred the mountain’s wrath? No… instead he took the horn. Placing it to his trembling lips, he let out a feeble parp. The Spectre’s voice rang out once more, “Woe to the coward who did not draw the sword before he blew the horn!” and with that, Dick was ejected from the mountain by a just of wind and died soon after (but not before relating his tale to the shepherd who discovered his broken body on the fell).

The myth of Arthur sleeping in a cave is not unique to the area (See this post), but the inclusion of Thomas – he that cannot speak a lie – reaffirms True Thomas in the lore of Eildon Hills.

There’s an origin to this myth and, just like Rhymer’s life, it’s mysterious. However, there’s no single telling. The ballad was written down by Sir Walter Scott and Robert Jamieson. Both took their versions from the same source, one Mrs. Brown – who transcribed the ballad from memory. However, the earliest written version comes from the 1300s, and another appears in the “Journey of True Thomas the Rhymer”, dated to 1652. This version differs from those of Scot and Jamieson quite a bit. Its tone is more archaic, less romanticised and is much lengthier than both.

The tale begins on Beltane ‘en – a time when the realms between mortal and faerie are transient. As Thomas lazes on Huntly Bank, taking in the summer bird song, he spies the fairest lady he has ever seen, galloping over the fields, accompanied by seven ratchets and three greyhounds*. She rides over a “livelong leye” – which is taken by some to mean an ancient ley-line, although the word leye is a medieval word that refers to a meadow invoking a sense of timelessness. It could refer to both, a play on words to enhance the ‘otherworldiness’ of his vision. The rider is splendidly attired in green silk, bejewelled velvet gowns and such finery that astounds Thomas. At first, believing this apparition to be Mother Mary, he runs to meet her at the Elden Tree (Eildon Tree). There, beneath the whispering branches of the old thorn tree, Thomas gets to his knees and begins praying. However, once the rider reveals that she’s not the Queen of Heaven, but Queen of another land, Thomas’ piety is quickly discarded. He is enamoured by her beauty and attempts to woo the Lady – but she warns him that should their lips meet then her beauty will fade. Despite this, his emotions get the better of him. He persists and she yields and seven times he lays beside her. Soon afterwards the fey Queen’s finery disappears, she is plainly dressed and her skin turns leaden, one leg is black, the other grey. Like a wraith she leads him on, into Eildon Hill – for there is a price that Thomas must pay, and he must remain with her for twelve months. Taking him upon her dappled-grey horse, they charge through knee-high waters for three days and nights (Scot and Jamieson change water to blood, and three to forty).

Arriving on firmer ground, Thomas’ hunger is so great that he rushes into an orchard, grabbing at the apples. But he is warned that should he bite the fruit he’ll be cursed. Instead, at the spectre’s invitation, he places his head upon her lap, and four paths are revealed to him. There is the path to paradise, the path to wellaway – (wala wa an Old English word for a ‘liminal space’, a ‘place of lamentation’, or ‘valley of sorrows’), and two other ways are marked for sinners. Mounted once again, they take a different path altogether, steering toward a fair land where a castle sits upon a hilltop. The Queen warns him that, in her country, he must only speak to her, otherwise he’ll return to Middle Earth (and, of course, the Fairy king must learn nothing of their tryst).

Upon entering this realm, the Queen’s beauty is restored, colour flushes her grey flesh, life returns like the sap of summer. In the great hall of the castle there is much revelry, with knights and ladies dancing to riotous music. There is laughter, joy, jests and banqueting. Here, Thomas enjoys the festivities and remains for many years (even though he believes it’s only been three days). But this state of affairs cannot last, seven years have passed and his time in Fairyland is up. If he doesn’t leave, the fiend of hell will come for his soul. He is returned to the Elden Tree, clad in green velvet, and carrying a harp. Not wishing to part with the Fairy Queen’s company, Thomas attempts to detain her through conversation. Each time she makes to go, Thomas asks her a question about the future, to which she answers – these take the form of prophesies**. Finally the Queen’s hounds become too impatient, but before she departs she agrees to meet him on Huntly Banks at a future time. As a parting gift, Thomas is given the inspiration that enables him to excel at the poetic arts.

He is credited with writing the ballad of Sir Tristem in auld Scots, and may well have been a bard to Alexander III. Indeed, one of his most famous prophecies concerned the Scottish king’s death, for it’s said that when Thomas returned from elfhame, he began uttering many prophecies – just as he’d heard them from the Faerie Queen’s lips***. The story goes that one day he was asked by a courtier to give prophecy. Agreeing, Thomas predicted that by noon the following day, a great calamity would befall Scotland. Sure enough, shortly after midday, tidings of the calamity came. As the king was skirting Kinghorn, along the coastal trail, his horse had stumbled, flinging him down the cliffs. With the death of Alexander III, a tumultuous series of wars began.

The remains of Thomas’ tower can still be seen in Earlston, and there are stones that mark where the Elden Tree stood. There was also a great hawthorn tree, a marvellous thing by all accounts, that stood on Rhymer’s old lands. Known as the Earlston Thorn, it was almost a 1000 years old. However, the owner of the Black Bull (on whose land it stood in 1814), decided to prune it back. This left it exposed to a severe gale, which uprooted the tree. A cloud must have passed over the minds of many there, for one of Thomas’ predictions went:

This thorn tree, as long as it stands,

Ercildune shall possess aw’ her lands.

Despite the heaps of manure locals packed around its base, and dousing the roots with whiskey, the tree still perished. Within the same year local merchants went bust and the common lands were repossessed – Thomas told no lie!

I like to entertain the idea that Thomas and the Fairy Queen did meet again, beneath the Elden Tree, with the Bogle Burn babbling nearby. Thomas the Rhymer is forever detained by the Faerie Queen, and “he still ‘drees his weird,’ in the underworld beneath Eildon Hill to this day.”

Notes:

* A ratchet is a medieval term for a hunting hound. Seven and three are magical numbers.

**Only some versions contain these. See Burton’s book for more on this.

***Many of prophecies attributed to Thomas have been surprisingly accurate. See, The Life and times of Thomas of Ercildune the Rhymer, by Elizabeth Burton who lists many of the prophetic verses and how they came about, such as the Battle of Otterburn, the seizure of Perth and the like.

References:

Early Scottish poetry – George Eyre-Todd

The Life and times of Thomas of Ercildune the Rhymer - Elizabeth Burton