Some years ago, after a visit to the city of Split, I was struck by an image of Capricorn that I chanced across in the historical museum there. Croatia was once occupied by the Romans, and Emperor Diocletian built an impressive palace there, the remains of which form the ancient heart of the city. It was an image I was to come across a few weeks later in the Hunterian Museum, on the grounds of Glasgow University. The museum houses an impressive collection of carvings that were found along the length of the Antonine Wall. This defensive Roman edifice once stretched across the isthmus between the Firth of Clyde to the west and the Firth of Forth to the east; basically spanning the narrowest point of central Scotland. The legionnaires there faced hostile tribes in the rugged terrain tot the north, mainly the Picti, Attacotti and Maeatae.

When the Romans decided to define their most northern frontier, they brought with them their pantheon of gods and goddesses. Many of these found their way onto carvings that were discovered by later archaeologists and antiquarians. Amongst these carvings was Capricorn – a symbol that began to tug at the corners of my subconscious.

Capricorn is a hybrid of fish and goat. In Greek myth it was said that Zeus placed the goat in the heavens for, originally, it had nursed him as an infant and was known as Amalthea (or Amaltheia), whose horns were stuffed with nectar and ambrosia. After her death Zeus filled one of her horns with the golden fruit from the island of the Hesperides, and it was thereafter known as the Horn of Plenty. However, the goat-fish constellation of Capricorn can be traced way back to ancient Mesopotamia, where it was a symbol associated with the Great god, Ea, whose name reflects his affiliations with the moon and water.

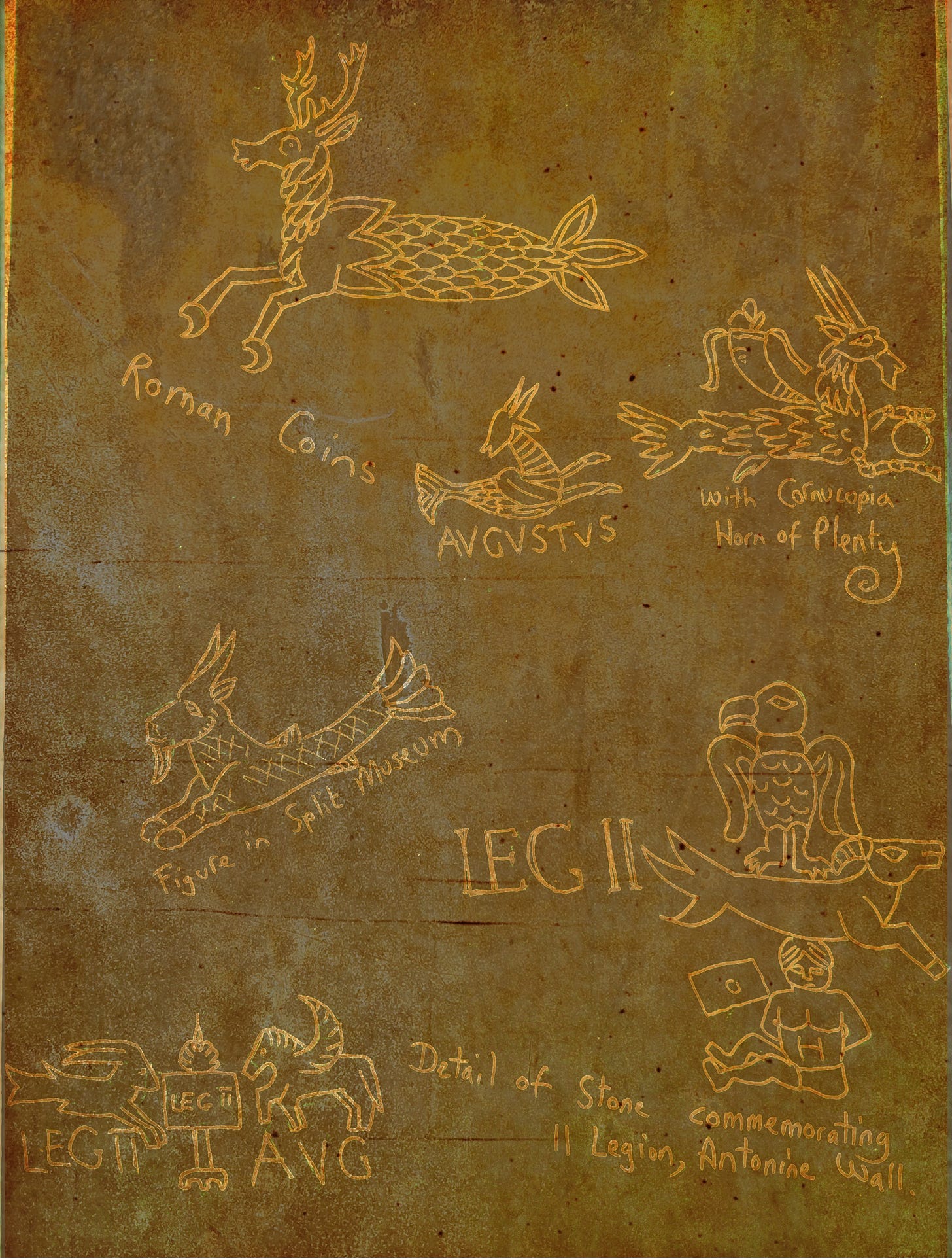

The Romans adopted much mythology from the Greeks. They changed many of the deities’ names, Zeus became Jupiter, Hermes, Mercury, etc. The symbol of Capricornus was adopted by the Legio II Augusta, who were formed in the middle of the 1st century BC and were involved in the subjugation of the Britons. Disgraced when they disobeyed orders during Boudicca’s rising, they were still honoured and respected in Rome. The Second were also active in the Roman city of Caerleon (once known as the Silurian capital of Isca, it was renamed ‘Fort of the Legion’), where a dedication to Mithras was unearthed. Mithraism was a popular creed amongst the soldiery, and both demanded lifelong loyalty and dedication. The third grade of Mithraic initiation was named Miles (the Soldier), and such cults and their associated imagery went with them as they marched north. The Roman mile fort of Housesteads, close to Hadrians Wall, includes Mithraic finds – which is not surprising, seeing as the II Legion built the town.

The II Legion was formed of men drawn from lands conquered by the Roman empire – in this case from Gaul, specifically the environs around the Celtic rath of Argentoratum (the latinised name of the Celtic village that existed before the Romans built over it). It’s a name that hints at the industry of the town: argentum, silver. During the time of Julius Caesar, these lands were in the hands of the Triboci, a people considered to have been Germanic, and might have formed part of the larger tribal amalgamation known as the Suebi. Since their subjugation, and subsequent drafting into the Second Legion, they’d found action during the invasion of Britain. There, they’d found themselves suppressing a people whose customs weren’t so dissimilar to their own. Both Celtic and Germanic tribes shared many ideas in common. Some of their deities possess a profound similarity, such as those found between the Lugh and Woden.

Capricorn was the symbolic and heraldic motif of the II Legion. They also chose another mythic creature, the winged horse, Pegasus. Interestingly, both these creatures appear on the Iron Age Celtic coins of Celtic tribes. Neither was such mythological imagery so displaced on the northernmost frontier of the Roman empire. Did legionnaires stationed there hear tales of strange half-horse beings that guarded local wells and rivers? Weren’t such spirits, later to be called Kelpies, already well known amongst the tribes? Weren’t they venerated and worshipped in their less folkloric aspect as powerful deities that both healed and harmed? Or were the carvings of the Romans so exotic and strange that they inspired their own legacy of stories and tales? And exactly how much lore was attached to Legion mascots or heraldic motifs? Today we tend to think of a ‘mascot’ as just an emblem, a lucky motif. What did Capricorn and Pegasus mean to the Gallic conscripts stationed far from their homes?* Could it be that such entities were already the romanised reflections of their own, more Celtic beliefs? Like the guardian of sacred waters that both healed and harmed?

Later Pictish art includes a number of mythological themed artwork, such a centaurs – some of which had been re-framed within a Christian context. Could the same be said of Capricorns that appear in pre-Christian Celtic art? Was imagery re-purposed to suit the beliefs of those people at that point in time? Or did it sit comfortably upon the shoulders of earlier notions of animist spirits? Or were they just emblems, bereft of much meaning?

Perhaps, when we look at the imagery that surrounds us, we see a similar trend. Mythological monsters re-appear, but they are seasoned with the themes of our era – and yet sometimes they’re still gripped in the teeth of the past.

Notes:

*It is likely that being the II Legio ‘Augusta’ they took their name from the date of Emperor Augustus, who was born under the sign of Capricorn :<

References:

Handbook of Classical Mythology – William Hansen

Mystery Cults in Roman Britain – John D. Drummond

Cassell Dictionary of Classical Mythology - Jennifer R. March

Illustrated Dictionary of Greek & Roman Mythology - Michael Stapleton

AND DON’T FORGET!

new Website The Starlit Under

Where you can purchase SIGNED copies of my Book!

Bha sin gle inntinneach! I especially like 'gripped in the teeth of the past.'

I never knew that about Capricorns, the ancient world is so fascinating.