When I used to trade in Edinburgh, I was invariably surrounded by stalls selling cheap silver jewellery. Most of it was made in Thailand and passed off as ‘Celtic*.’ Each stall had little cards displaying the meanings of the designs. That given for Celtic interlace was always ‘eternity’. If you’d ever had the chance to visit my stall and listened to me waffle on, you’d get the longer version, including that I believed knot-work reflected the thread of life and a sense of connectedness.

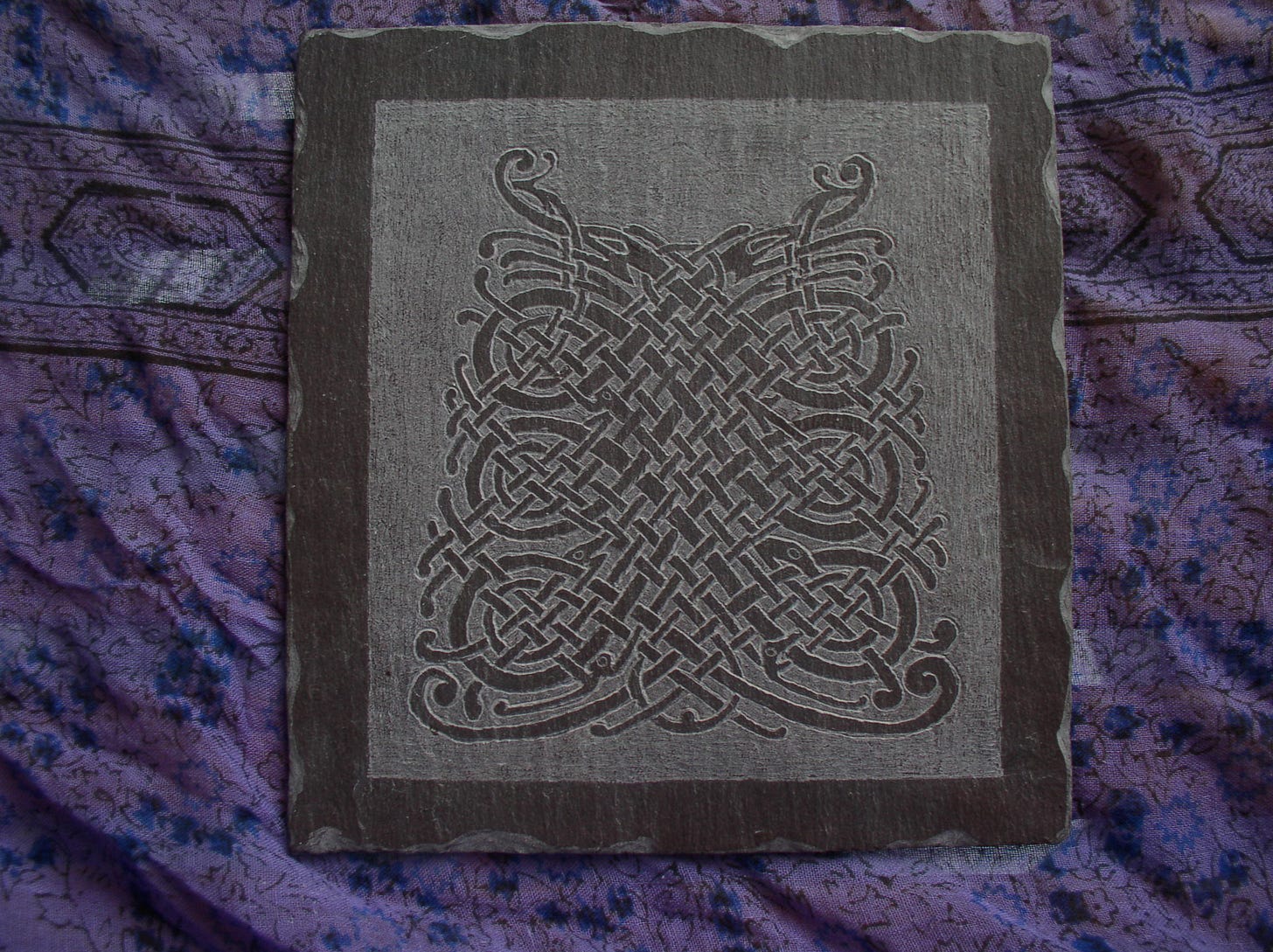

In all my years carving I've restricted my use of knot-work. Partly because it’s complicated and time consuming. I also feel knots have become synonymous with Celtic art, and this isn't wholly true. Knot-work is a later development and was never restricted to the tribes we nowadays term Celtic. If anything the interlace was borrowed from other cultures.

Celtic interlace is a mutation of the Lombardo-Byzantine style that was developed by the Gaelic scribes in Ireland and Britain. The art-form flourished, reaching the exquisite heights we see in the art of that period. However, much of the subject matter was overwhelmingly Christian, with mythological imagery used out of its original context. Despite this, the knot and its use rested on much older concepts.

Many ancient cultures saw life as a vast tapestry. The threads of fate were strung together, woven; never remote, never isolated, but linked by invisible threads. In the East, Tao was the chain of all creation, while the ancient Babylonian word, markasu, means both link, cord and, in myth, “the cosmic principle that unites all things.”

“Do you know the string on which this world,and the next and all beings are strung together?”

Upanishads 3:7:1.

In some cultures, such as the Norse, female principles were given charge of the threads of fate. Odin was bound and hung from the world tree. There’s evidence of cult practices amongst ancient Germanic tribes that involved binding rituals. In one of the earliest human sculptures of a ‘goddess’, the hands of this voluptuous female appear wrapped in a cord, hinting at such an ancient ritual.

In the context of Pre-Christian Northern Europe, Celts, Saxons and Norse, all used interlace in their art. With it they were expressing something that is very profound and reflects the way they viewed the world. Everything was connected, whether it be the shades of one’s soul or the spirits of the river. Not only were the living linked, but past and future too. The images that adorned weapons and jewellery were the microcosm of this concept. Animals, monsters, plants, all were inevitably joined by the invisible web of energy. The Germanic tribes knew this as the web of Wyrd.

In this context it’s little wonder that magicians and sorcerers of the time sought to bind with spells. Magic songs and chants were woven. Battle magic sought to tie the threads around warriors, to leave them spellbound and unable to act, knotted in fear. The etymology of many magical terms is often linked to such imagery.

Thus Knot-work could also be used as a talisman for protection. They could be used both beneficially and detrimentally, to curse as well as heal. The more complex the interlace, the more effective it would be. If we also take the primary function of a knot in a piece of twine, hempen rope, or blade of grass, we find another meaning. By binding one to another, just as a marriage is a binding of entities, legally and emotionally – some later knot-work designs from the Highlands of Scotland symbolise this union.

This sense of place and connectivity is reflected in quantum physics. David Bohm’s book, “Wholeness And The Implicate Order”, likens the rush of thoughts to a river, in which there are eddies and vortexes of thought, yet all are connected and moving. Although our mind isolates fragments of thought into phenomena, this isn’t actually so. In the quantum world everything is linked, nothing is separate. This ties in with Chaos theory and the famous quote of the butterfly, whose tiny wings could kick-start hurricanes across the globe. Such theories sit comfortably alongside the idea of the fabric of the universe being an interlace of connectivity.

Sometimes I have the uncanny feeling that at an instinctual, intuitive level the ancient peoples grasped fundamental principles of existence. Not fully understanding the physics behind the metaphors, they identified its essence in their cosmologies all the same.

I feel this idea is important in our day and age. Not only in relation to symbolism, for nothing is achieved in isolation and ideas move like people. Religions, creeds, philosophies – all inspire and alter art, reflecting the evolution of human perspectives.

Notes:

*How can anything made in Thailand be ‘Celtic’? It’s Thai, even if it’s of a Celtic design.

References:

Celtic Art In Pagan And Christian Times – Romilly Allen

Lost Beliefs Of Northern Europe – H.R. Ellis Davidson

The Real Middle-Earth – Brian Bates

Liked that? You might also like this one then too - The Hands of the Fates

Elsewhere I have read that Celtic knots are a Nordic import (specifically Viking era), that Celtic designs relied heavily on spirals. I don't know how reliable that source was or if they overstated their claim. You mentioned an earlier Germanic and Byzantine influence as well. It's something I've been meaning to ask you about. So, it was a pleasure to see the subject come up.…I don't take your thoughts on the ancient world as authoritative—nor anyone else's—but I know you've dug deeply through a vast array of sources and are more trustworthy than many people writing on the subject. I think this is where I say something about wishing your pieces were longer and more in depth. I know, that goes against your plan for these posts to be just a taste. I'm a glutton by nature. Especially for information and ideas.…A really enjoyable piece.

I really love this piece, thank you for sharing it. This quote especially I agree with "Sometimes I have the uncanny feeling that at an instinctual, intuitive level the ancient peoples grasped fundamental principles of existence. Not fully understanding the physics behind the metaphors, they identified its essence in their cosmologies all the same."