There was always something compelling about the Dorak Affair. Archaeologists* and academics were, and to some extant still are, seen as untouchables. They reveal the treasures of the ancients, claimed by the earth and therefore they share an intimacy with their discoveries most of us will never have. Carrying the torch of science, many will postulate expansive theories of history, based on their material finds.

And yet in the late 1950s an archaeologist named James Mellaart was on a train in Turkey. He noticed that a girl in his carriage was wearing a Bronze Age bangle. Striking up conversation she told him that there were more old items at her place. He accepted the offer to have a look and spent the next several days examining the artefacts. Although the girl, whose name was Anna Papastrati, wouldn’t let him take pictures, Mellaart made sketches and notes. The pieces, Anna explained, had been dug during the early 1900s at a place called Dorak, south of Marmaris.

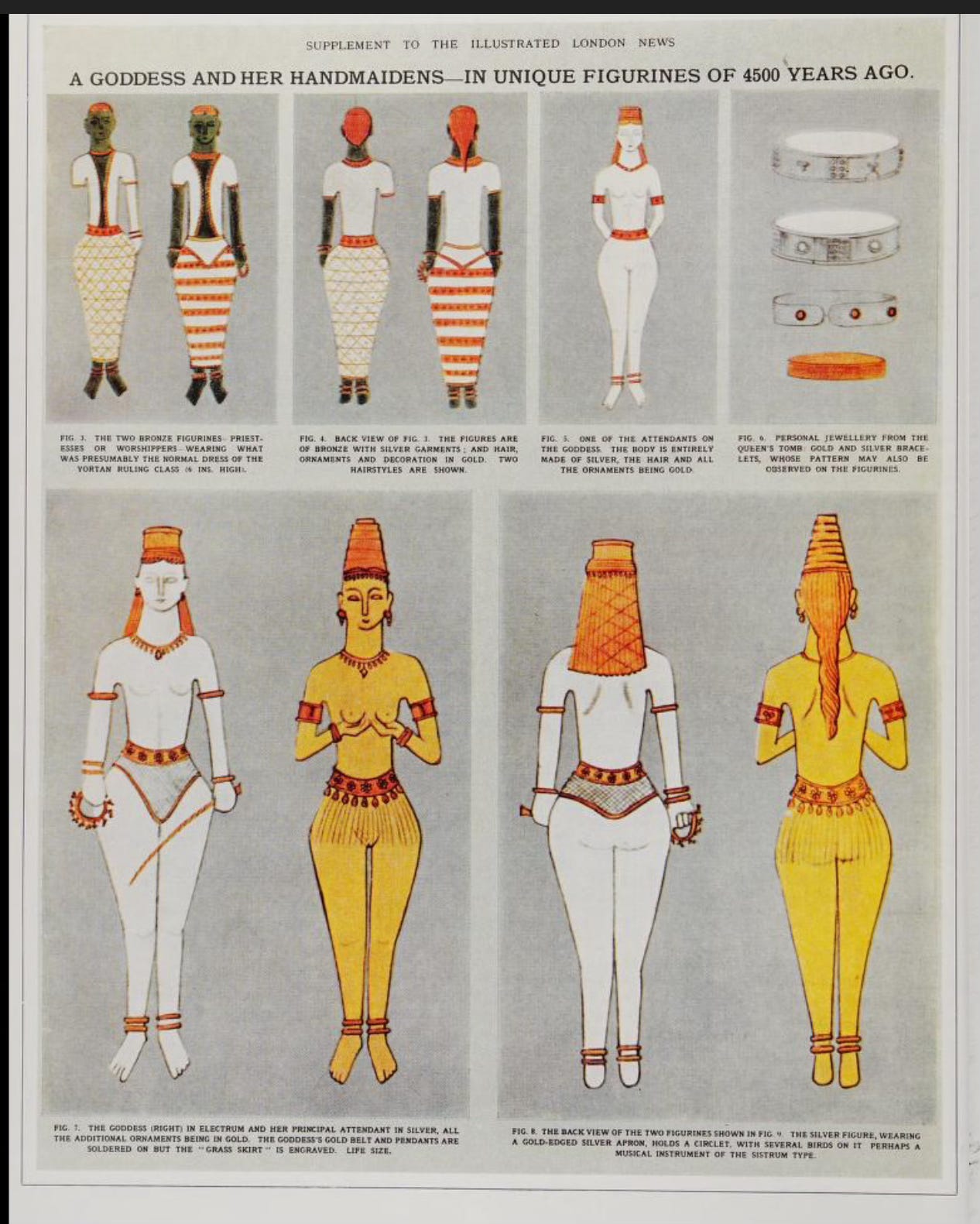

The story was taken up by Illustrated London News in November 1959 (Turkey’s second largest news outfit at that time), with artwork displayed in a lavish four-page spread. The article caused a stir, not only in the archaeological world, but amongst Turkish authorities. Attempting to locate Anna, the authorities drew a blank, arriving at the conclusion that Mellaart was involved in a smuggling ring. However the address given as Anna’s existed in two different parts of the city – there were two Kazim Direk streets. The police had been to a commercial site, where there were no private houses. A Turkish journalist found a source who said he’d seen Mellaart digging at Dorak. Villagers were also interviewed. They said they’d seen an overweight white guy in Khakis wandering the area. An article appeared in the same newspaper, this time accusing Mellaart of smuggling out a treasure worth millions.

The trade in illicitly trafficked archaeological objects was a major concern of the Turkish government and strict rules were in force to try and curb the trade. However Mellaart denied any involvement in illegal activities. He was after all the head archaeologist at a settlement he’d discovered near the Syrian border. The ruins of Çatalhöyük were changing what was known about Neolithic history at the time. Mellaart’s discoveries there were unearthing the structure and early religious remains of its inhabitants from 7400 BC. It is said that he practically discovered the Neolithic in Turkey. Everything he did was pioneering and he wrote a series of groundbreaking books, detailing his finds across the country.

The political jostling began, with those for and against Mellaart. His genius was indisputable, and he had a knack of finding ancient remains and unearthing Bronze age sites. He was also arrogant and headstrong – a man who couldn’t tolerate those who didn’t share his intellectual capacity. And something wasn’t quite right. It didn’t help that he’d lied to a colleague about the artefacts, saying that the event had occurred several years previously, which it hadn’t. When the lie came to light Mellaart explained that having just been married, to admit that he’d spent several nights in the company of a young woman would’ve put him in an awkward position.

The debate raged on, with Mellaart being pulled from any involvement with Çatalhöyük, and although he disappeared off the scene, turning to teaching and writing instead, the scandal followed him and the rumours continued. Articles appeared, books were written and then, time passed on. The affair became buried beneath layers of newsprint and celebrity gossip. Today it is all but forgotten. James Mellaart passed away in 2012.

However, this is where things took a turn. The mystery had remained as such for decades, with no one certain if he’d actually smuggled the pieces and sketched them before he had sold them. If so, had Anna been made up? Or had Anna been a plant, waiting on the right train at the right time to draw Mellaart, ever the expert, into validating a collection of stolen objects? Or was he telling the truth? Many scholars believed the items he’d described and drawn were real, never doubting their authenticity. They spoke of a valuable royal Bronze Age burial.

The thing is James Mellaart was a collector, a hoarder of documents and notes. He kept everything. A scientist, Eberhard Zanger was tasked with sorting through the contents of Mellart’s study after his death. It was crammed with folders relating to old digs and neolithic sites. As they sifted through the contents one thing became clear: James Melaart was a forger. Despite his high standing, and the respect he’d gained in the academic world at the time, he’d invented things, such as a mural at Çatalhöyük, which never existed. Inscriptions he’d translated in the ancient Luwian, were also cast into doubt. It was as if he’d inhabited a fantasy world, in which ground breaking discoveries could be accentuated with a little added spice. Given the evidence it was obvious to the investigators that the Dorak finds too had been invented… the whole affair had been a product of Mellaart’s imagination.

But why? In the late 1950s here was a man coming into his fore, an expert in his field, rising to fame, giving lectures, revealing the treasures of the Neolithic sites of Çatalhöyük and inspiring a new generation of archaeologists. The sites he uncovered are real, and without doubt he paved the way for new insights into the Neolithic era. But it wasn’t enough. For whatever reason (superiority?arrogance?) Mellaart invented a strange scenario of the girl on the train. For me the story reveals a humanity behind the academic. The bastion of Archaeology is a great science, revealing the past to all. Archaeologists are people, prone to the same flaws, failures and genius as the rest of us. The Dorak Affair reveals a human side to those who sift through the debris of the the past. It’s as valuable an insight as the bovine skulls that line the walls of Çatalhöyük.

Notes:

*Except for Phil Harding – He’s almost semi-divine :>

References:

The Strange Case of James Mellaart, or the Tale of the Missing Dorak Treasure – Kenneth Pearson & Patricia Connor (Horizon Magazine 1967)

James Mellaart: Pioneer… and forger – Eberhard Zanger (Popular Archaeology )(https://popular-archaeology.com/article/james-mellaart-pioneer-and-forger/)

The Dorak Affair – Kenneth Pearson & Patricia Connor

The world of archaeology is full of these stories, even on smaller scales. When I worked as an intern at a famous prehistoric department in northern Italy, there were a lot of artifacts "lost" (and sometimes found).

We were moving from the old labs to a new venue, and I remember pulling a cardboard box from under a bookshelf. Inside there was a skeleton. I called my supervisor, who just commented, "Oh, there it is. I lost track of it a few years ago." It was a Bronze Age woman from a pile-dwelling site near Lake Garda. A few days later, we found another skeleton (still in its plaster cast) of a Bronze Age man affected by dwarfism, thought to be lost since 1980.