My Dad trained guide dogs for the blind in the 1970s, so I grew up around them. When my parents opened a boarding kennels I was sequestered to walk dogs and clear up their many poops. I was always amazed at the variety of different dog breeds and how much their temperaments varied. It’s incredible to think that the domestication of wolves has given us the myriad of breeds existing in the world today*. Our canine compadres were probably lured into symbiotic union with humans during the Palaeolithic era. But our earliest glimpses of them in art comes in the form of rock carvings from an archaeological site in Turkey.

Close to the troubled Syrian border, Göbekli Tepe is thought to have been an ancient sanctuary of considerable size and importance. The architects and builders of this structure erected some two-hundred 6ft, 20 ton, t-shaped posts in a series of circles. Some of these pillars are decorated with animals, with the function of guarding the dead interred within. Evidence of ritual use has dated the site as having periods of use between 10,000-8,000 BC. Amongst the carvings are dogs.

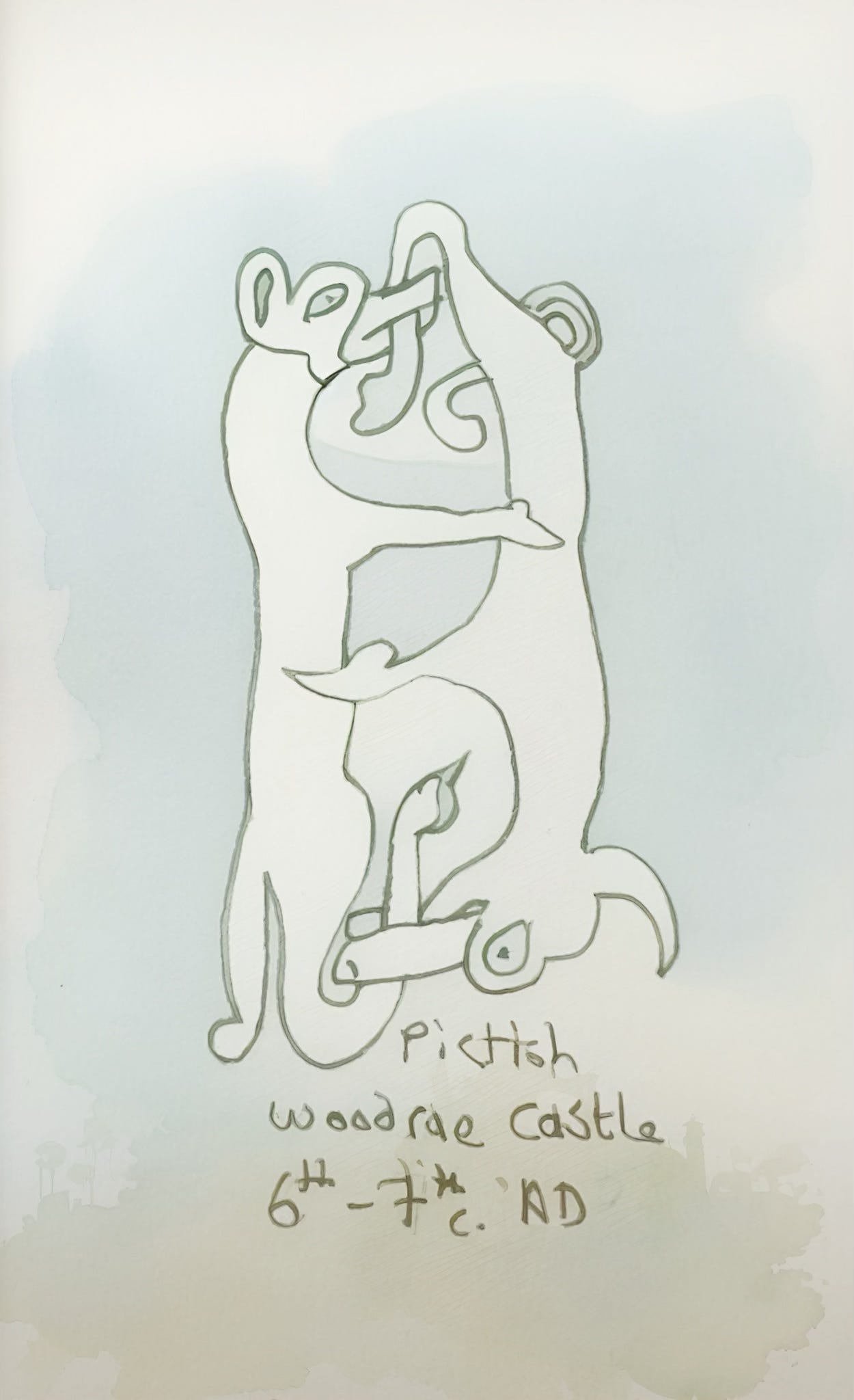

Suffice to say domesticated canines have enjoyed a long history as human companions. They turn up in many myths and legends across the globe, such as the dog-headed Egyptian God Anubis and three-headed Cerberus who guards the gate to Hades. In the British Isles dog bones were interred within burial graves five-thousand years ago. The bones were mixed amongst the human, and sometimes other animal bones are also present. Evidence shows that human bodies were left exposed to the elements, and later the bones were collected and then stored in burial chambers.

At the archaeological site of Flag Fen, near Peterborough, dog bones were found at the base of a mysterious wooden walkway that formed part of a Bronze-Age religious complex. Thousands of wooden posts had been driven into the marsh, holding aloft a walkway linking a sacred burial isle to the mainland. The remains of the dog(s) had intentionally been buried in the foundation. Such burials are not unknown throughout the ancient world. Were the bones placed there to guard the site? Or were they offerings to the deities worshipped there? Was the dog a pet? Or did it serve another symbolic function?

Iron Age ritual wells have yielded remains of dogs that were buried in pairs – hinting at a dualistic symbolism and confirming their funerary associations. From Romano-Celtic Britain there’s also evidence to suggest that dogs were closely associated with the healing god, Nodens. Effigies of dogs have been found at religious shrines dedicated to him. It’s likely that at these temples sacred dogs, belonging to the sanctuary, would be allowed to lick the affected area of the worshipper. Dog saliva contains the enzyme lysozyme, which helps defend wounds from bacterial infection. It’s also recognised that the presence of a dog can reduce levels of stress. Other healing deities were associated with dogs, such as the goddess Coventina. Their imagery appears at many Gaulish healing shrines.

Symbolically dogs are naturally associated with loyalty and bravery (like in the epic tale of Gelert the Hound). For the Celts, dogs encompassed a triad of significance: hunting, healing and death. In the Welsh tradition the Cŵn Annwn** were huge white wolfhounds with blood-red ears – the Hounds of Annwn, the Hades of the Celts. These spectral beasts hunted the mountain of Cadair Idris and their howling foretold the death of those that heard them. It’s likely that such imagery inspired later folkloric stories of the Hounds of Hell. The otherworldly aspect of the dog is also reflected in Romano-Celtic statues of the hammer god, Sucellus, which are occasionally accompanied by a triple headed-hound, or those that accompany the North Sea goddess, Nehalennia.

With regard to the hunting prowess of dogs, they feature prominently in many old sagas, and appear with statues of the Goddess Diana at Cirencester and London. The wolfhounds of mighty heroes and war-bands appear in many Celtic myths, such as those of the Fianna. In these tales care is taken to document the names of the hounds, pointing to the affection and respect they were accorded.

Like the wolf, dogs were sometimes associated with battle. There’s even reference made to the Lombards having cynocephali (dog-headed warriors) amongst their ranks. There were also the Heodeningas or Hiadnings, dog warriors who would fight every day until the end of the world – these warriors are almost indistinguishable from Odin’s einheriar.

While the dog is renown for its use in the hunt, it’s intriguing that they were once more widely known for their affiliations with the Underworld. Would such insights have helped me as a stroppy teen, bemoaning my lot as I stooped to remove another reeky dog shit? Could such insights have armed me with a deeper layer of meaning? Maybe my days working in the kennels would’ve been more profound – knowing that I laboured in the company of the Hounds of Hell would have upped the kudos of the job!

Notes:

*I admit, from wolf to Chihuahua is a big leap!

**In Welsh folklore the Cŵn Annwn are also associated with migratory geese.

References:

Symbol & Image In Celtic Religious Art – Miranda A. Green

Pagan Religions Of The Ancient British Isles – Ronald Hutton

Ancient Germanic Warriors – Michael P. Speidel

An Archaeology Of Images – Miranda A. Green